"This past summer I heard several news stories about environmental groups calling for an end to fossil fuel subsidies. Then the political campaigns picked up on it and started going back and forth over failed green energy subsidies and 'corporate welfare' to rich oil companies. Does the US really subsidize the fossil fuel industry, and if so, how much?"

-Lauren from Brooklyn-

Without wishing to sound like a late-90s Bill Clinton, the answer to your question depends on the definition of the word "subsidy". We can look at it from the point of view of Webster's definition: "a grant by a government to a private person or company to assist an enterprise deemed advantageous to the public", or the Oxford definition: "a sum of money granted by the government or a public body to assist an industry or business so that the price of a commodity or service may remain low or competitive". The World Trade Organization, the international entity charged with monitoring government interference in markets and disciplining those actors who unfairly manipulate those markets to the benefit of their own companies or industries, required seven pages in its 2006 World Trade Report to adequately summarize their definition of a subsidy. For the purpose of answering your question, we will consider a subsidy as follows:

1. A direct action or specific inaction by the government (an example of "inaction" would be a government choosing to not collect a full royalty or tax that laws otherwise require)

2. That directly improves the financial health of a private company or industry through a reduction of cost directly attributable to the action of that company or industry or an increase in revenue directly received by the company or industry from the government (we will ignore money given to consumers specifically for the purchase of a commodity which would indirectly improve the health of the company or industry)

3. Whose purpose is maintaining or improving the financial health of a company or industry (we will ignore infrastructure improvement projects which do improve the financial health of a sector, but whose primary purpose is a public good associated with the infrastructure in question...infrastructure specific to an industry will be included)

I should note that much of the discussion from this past summer, especially centering around the Rio+20 meetings on climate change and policy, focused on worldwide subsidies for fossil fuels. In analysis by National Geographic, again using a different definition of subsidy, the US falls far behind Iran, China, Russia, and India in terms of how much we spend on subsidies. The NRDC estimates that worldwide, governments spend about $775 billion in subsidies. In the US, the amount is not quite so clear, as we will see.

The most fundamental analysis of US subsidies comes from the Environmental Law Institute which looked at US federal support of the fossil fuel and renewable energy industries over the course of 2002-2008. They found that over that timeframe, the US government provided $16.3 billion in direct spending to benefit fossil fuel companies (mostly in research and development), another $53.9 billion in tax breaks, $2.3 billion in research into carbon capture and storage (a technology meant to benefit the coal industry), and $16.8 billion in support to the corn ethanol industry (which, since it emits carbon dioxide and is an additive meant to support the gasoline industry, I will consider with the fossil fuel subsidies). This average of about $15 billion a year agrees with the analysis from National Geographic.

With a pretty solid $15 billion estimate, why is there so much talk about as much as $2.1 trillion in subsidies to fossil fuels? One word....externalities.

Economically, an externality is a cost or benefit associated with an industry that is not reflected directly in the market for that industry. Pollination provided by bees that a keeper specifically raises for honey, or development of the internet from research funded for military purposes show positive externalities. Lung cancer deaths from second-hand smoke, or increased urban blight from the presence of liquor stores exemplify negative externalities. In general, for a consumer to make a "rational" choice in the marketplace, we want all the costs associated with a product or service to show in the price paid by that consumer. In the case of fossil fuels, there are several consequences of fossil fuel use that the industry does not pay directly, and therefore, the consumers of those goods do not see in the price:

1. Increased health care costs: the National Academy of Sciences estimates that the US spends $120 billion each year on health costs associated with fossil fuel use (see their 2010 publication Hidden Costs of Energy for more details on externalities). Although some of this comes from individual consumers, the government, as a large payer in the health care industry, bears much of this cost.

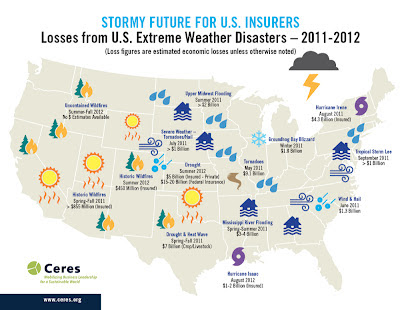

2. Increased costs to make repairs after extreme weather events: In a report from Ceres, the insurance industry (including government and private insurance) stands to pay out about $20 billion in claims in the US related to extreme weather events after paying out $34 billion last year. Of the $20 billion, the US government is slated to pay about $15 billion.

3. Changes in commodity prices: as crop yields decline, and growing areas shift, prices climb with demand remaining high. Studies showing that crop yields decrease with climbing temperatures suggest a role for climate change in the fluctuations in food markets.

4. Pollution cleanup: A 2011 assessment published by the American Economic Association, put the annual cleanup costs associated with US fossil fuel industries at about $10 billion dollars, noting that the cost was more than the benefit received from the industry. The government performs this cleanup in the current economic model.

5. Restoration after mining operations: when an area is strip-mined or used for drilling natural gas or petroleum, the operation leaves a mark on the landscape. Although some oversight agencies requires some level of restoration, most do not. We are left either with a degraded environment that cannot perform the services it once did, or a large cost of cleanup to be covered by taxpayers.

Depending on the source you use, and the value placed on each measure, this can total as much as $500 billion in US economic support for the fossil fuel industry. Our economy has recently shown much resilience to drops in vehicle miles travelled and electricity usage...we can do more with much less. As long as these companies remain profitable, there is no foundation for covering their direct costs in this way. If we eliminate the tax breaks, use insurance markets to assign health and environmental risk directly to producers of pollution, apply carbon taxes as necessary to help consumers pay for the impacts caused by industry, and target stimulus to developing industries that could result in higher levels of public good, we have a better shot of creating a stable, livable economy.

No comments:

Post a Comment